New Article: The Birth and Burial of Evolutionary Science in Australia

Activists of often mostly European ancestry have appropriated prehistoric cultures and are systematically destroying fossils vital to understanding the evolutionary heritage of all humankind.

This article by Jack Mungo was published at Palladium Magazine on October 17, 2025 and will also feature in our Fall 2025 print edition PALLADIUM 19: Long History. Subscribe now to receive your copy of our latest edition.

In March 2025, the Australian government quietly buried its last collection of Pleistocene human fossils in an unmarked grave. These remains were of Homo sapiens who had shared the Earth with Neanderthals. But they went into the ground with little media coverage or protest from the global scientific community, who knew better than anyone that these delicate, carefully reconstructed fossils would not last long in hostile conditions.

The significance of this loss is hard to overstate. Australia is a unique piece in the puzzle of human origins. It was colonized by modern humans before Europe, but it remained almost entirely isolated, preserving many aspects of human culture and genetics that vanished elsewhere. As Charles Darwin observed, “the Australian aborigines rank amongst the most distinct of all the races of man.”

Following the British settlement of Australia, museums and universities accumulated collections of both historical and ancient remains. Most material came from southeast Australia and Tasmania, where the once-numerous tribes had suffered enormous losses and even extinction. Today, these thousands of bones, mummies, and fossils have almost all been buried or cremated; genetic “biographies” that were burned before they were ever read.

Australia’s Lost Scientific Heritage

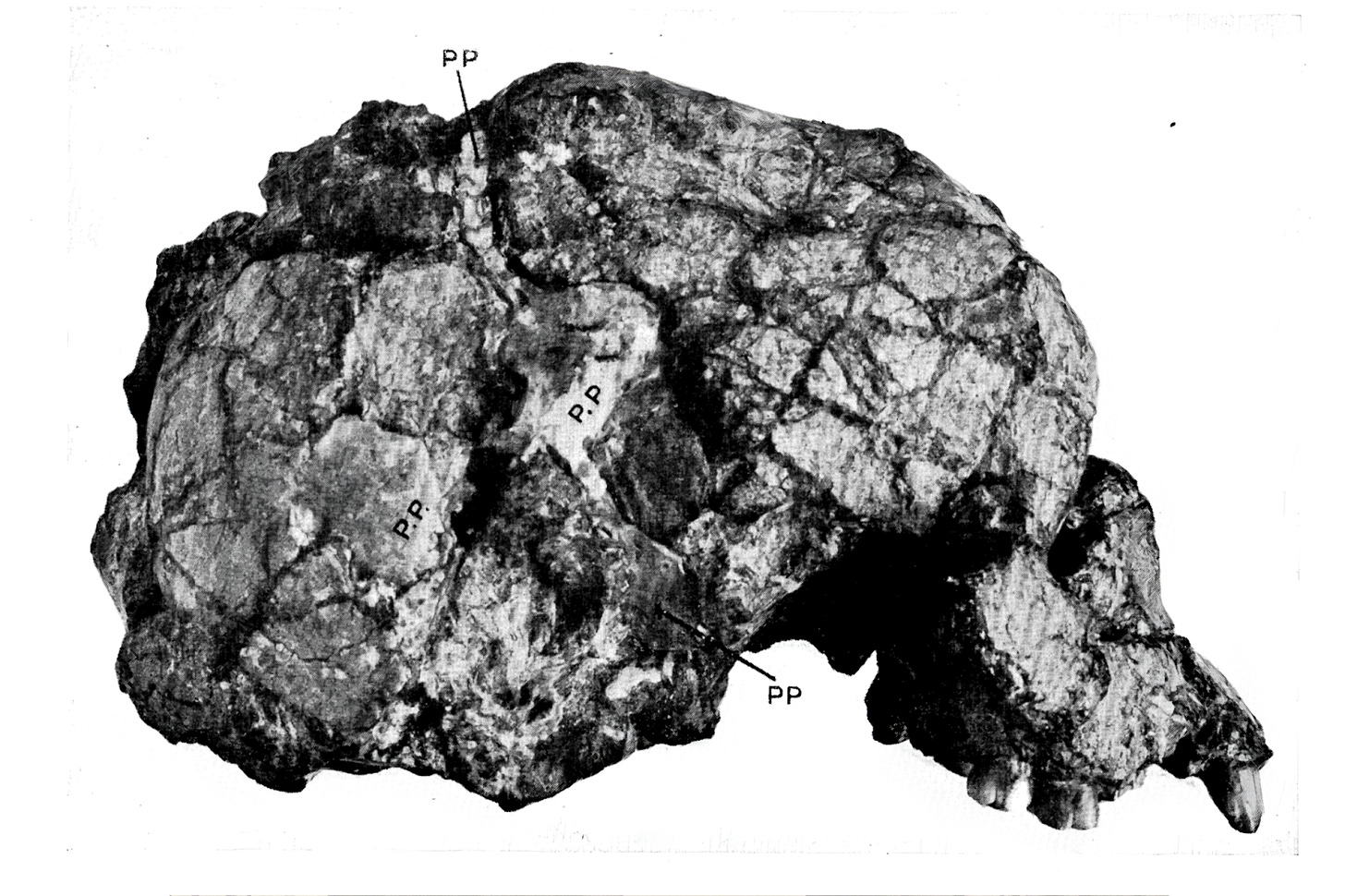

Early Australian paleoanthropology was characterized by chance discoveries. In 1884, the Talgai skull from Queensland was one of the first human fossils found anywhere in the world, seven years before Homo erectus was discovered on the nearby island of Java in Indonesia. It belonged to a teenage boy killed by a violent blow to the head around 11,000 years ago. While the cranium was similar to recent Australian foragers, the palate, canine teeth, and facial skeleton had archaic traits. Sadly, its damaged condition prevented in-depth analysis.

After World War I, Australian archaeology was led by researchers Norman Tindale and Fred McCarthy. Many finds came from enthusiastic amateurs such as the pastoralist George Murray Black, who dug up and donated hundreds of skeletal remains during a twenty-year period. In the 1960s, John Mulvaney, a university-trained archaeologist, championed a more systematic approach. He strived to distance his field from “antiquarians” and grave robbers, shifting power from museums to universities as the primary centers of archaeological research.

As more fossilized remains were discovered, sometimes hidden within collections of recent bones, comparisons could be drawn between ancient Australians and the ones first encountered by Europeans. While sharing some skeletal similarities with recent populations, ancient individuals were often distinguished by “heavy-boned faces, enormous teeth and jaws, receding foreheads and flask-shaped skulls.” The mosaic of modern and archaic traits, seen to a lesser degree in contact-era skulls, emphasized the importance of these fossils to evolutionary history. The largest collections included Kow Swamp (c. 20,000 years old), Coobool Creek (c. 14,000 years old) and Willandra Lakes (c. 43,000 to c.14,000 years old).

One exceptional specimen was designated “Willandra Lakes Human 50,” also known as Garnpung Man. It shared traits with Javan Homo erectus and was more similar to ancient humans from Skhūl Cave in Israel than contact-era Australian foragers. At an estimated 26,000 years old, it may have had significantly more Denisovan ancestry than the 2-4% seen in recent Melanesians and Australian foragers.

The morphological variability seen in the fossil record led some researchers to hypothesize multiple migrations into Australia, with some genes coming from Homo erectus and some from ancient Chinese Homo sapiens. Others argued for local adaptation of a single Homo sapiens founding population. This debate featured significantly in the global discourse between proponents of “multiregional evolution,” which claims that modern Homo sapiens evolved simultaneously in multiple parts of the world, versus the “Recent Out of Africa” theory, which holds that Homo sapiens first evolved in Africa and then spread into Europe and Asia, replacing older human species.

What made these collections particularly valuable was their status as a comparative series. The ability to compare a group’s average morphology across eras and regions allowed scientists to track evolutionary changes and adaptations in ways that singular remains could not.

In the late 1990s, DNA analysis entered the scene. A 2001 study of the approximately 40,000-year-old Willandra Lakes Human 3, also known as Mungo Man, suggested he was not ancestral to any recent people, including contact-era foragers. Though now contested, this finding highlighted the capability of genetics to address old controversies while sparking new ones.

But despite their great significance, these fossils were only available to science for a brief moment in time. In 1984, as the first specimens began to be reburied, paleoanthropologist Peter Brown protested: “Sacrifice of this material in the search for short term power or political expediency is criminal and should be considered an offense against all mankind.”

And scientists weren’t the only ones interested in preserving the fossils. Badger Bates, a descendant of Australian foragers, stated in 1985: “We never came over the sea in a boat, but we was in Australia since the beginning of time. That’s why I’d like to see ancient human remains studied—because I think they could give us proof that the whitefellas are wrong about us.”

Identity Politics in Australia

To understand why these fossils were reburied requires an understanding of the various definitions of “Aboriginal” and how this identity and legal class has changed over time. Before British colonization, no equivalent terms to “Australian,” “Indigenous,” “First Nations,” “Aborigines,” or “Aboriginal” existed among Australia’s over six hundred tribal populations. As anthropologist Norman Tindale noted, each tribe was formed of culturally similar but mostly autonomous clans and maintained a localized “us and them… we and aliens“ worldview.

One thing they did have in common was a lack of agriculture: they lived by hunting, fishing, and foraging. When the British arrived in Australia, they called the people they met “native” or “aboriginal” as they had in other colonies. Today, three separate groups are often conflated under the single term “Aboriginal.” These are:

The ancient humans who first settled the continent.

The contact-era foragers encountered by British colonists.

The citizens currently classified as “Aboriginal” by the government.

This third category was formed when Australia’s 1967 constitutional referendum empowered the federal government to make laws for people of the “aboriginal race.” The government subsequently changed its definition of Aboriginal from requiring over 50% forager ancestry to a new standard based on self-identification, any degree of biological descent, and community recognition. This pivotal change meant even those with minimal forager ancestry could join the Aboriginal “class.” A separate legal class, “Torres Strait Islanders,” was eventually split off, with both classes now subclasses of the “Indigenous” slash “First Nations” class.

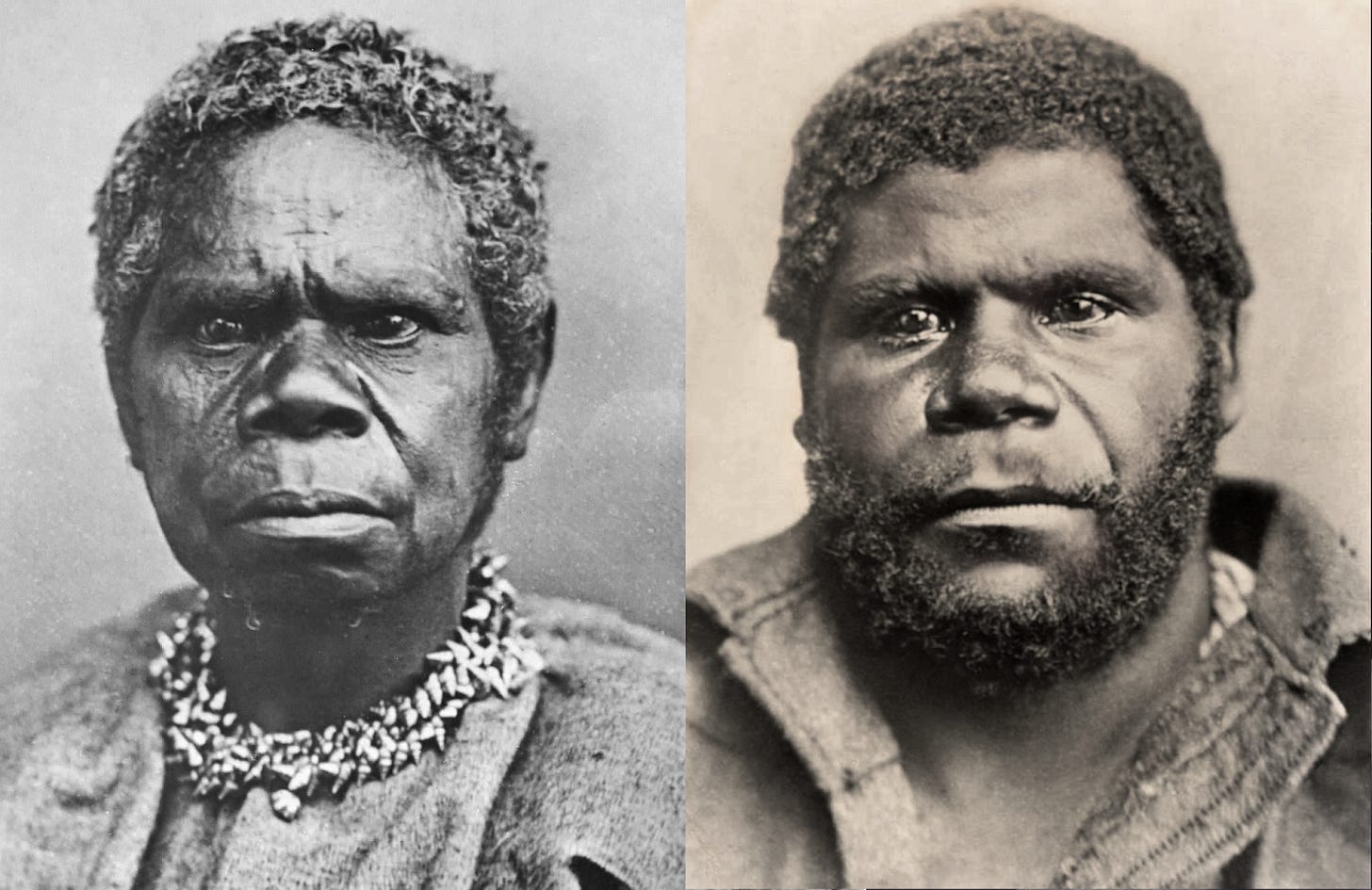

Before 1967, “Aboriginal” was a legal class with restricted rights. To avoid stigma, many mixed-descent Australians kept their forager ancestry a secret. But as membership criteria relaxed, and additional rights and privileges granted, more people publicly claimed forager ancestry. The Indigenous population exploded and is still growing faster than birth rates can explain. This is the result of people joining the class as adults, sometimes inspired by family legends or personal conviction. Also notable is that most Indigenous-class Australians marry non-Indigenous-class partners, but 90% of children from these unions are assigned Indigenous at birth. Archaeologist Josephine Flood observes that “Many people who identify as Aboriginal have white skin, blue eyes, narrow noses and blond, brown or red hair. Others resemble Japanese, Chinese, Melanesians, Polynesians, or Afghans.” In 2015, a government official estimated that 15% of Indigenous citizens had no forager ancestry whatsoever.

At the time of the referendum, all forager descendants had been granted equal rights, including the ability to vote, but many still felt discriminated against. Some who had both forager and European ancestry had been forcibly removed from their families and given a Western education. Those of mostly forager ancestry lived primarily in remote regions, while mixed ancestry was the norm in places like New South Wales, Victoria, and Tasmania, where the forager populations had been devastated by violence and disease.

Tasmania was especially notable, with the majority of forager descendants having 95% European ancestry. These descendants of British sealers and kidnapped forager women were not considered Aboriginal by themselves or the government. This changed in 1972, when activist and lawyer Michael Mansell, aware of the new definition, began researching family trees and encouraging his relatives to identify as Aboriginal. Not all were easily persuaded. Many identified as “half-castes” or “white” while others as “Cape Barren Islanders.” One islander, Annette Mansell, said in 1978:

“I’m not Aboriginal. I’m only a descendant of one. Just compare the Aborigines that were here with their descendants today. There’s a hell of a difference. There are no Aboriginals and there’s not much in any of us.”

But Michael Mansell, despite or because of his blue eyes and fair skin, strongly disagreed, arguing that “the identity issue is crucial.” If forager descendants wanted more than welfare and equal rights, they needed to form a united front, no matter their DNA. Using strategic essentialism, activists helped shape the narrative of a monolithic “Aboriginal people” stretching across the entire continent, back into the primordial “Dreamtime” and, most importantly, into the present. Because only if the government recognized them as Aboriginal could these young activists claim to represent the displaced contact-era foragers and begin lobbying for “positive discrimination,” or what is known in America as affirmative action.

Descendants in remote regions focused on gaining land rights, but in urban areas the class struggle centered on compensation and acquiring the remains of foragers preserved in museums and universities. For as Michael Mansell asked, “If we can’t control and protect our own dead, then what is there to being Aboriginal?”

How Australia Lost Its Fossils

While connected to earlier civil rights activism, the campaign that eventually destroyed Australia’s fossil record emerged from the Baby Boomer counterculture movement of the 1960s and 1970s that challenged “the defining social institutions” of Western society.

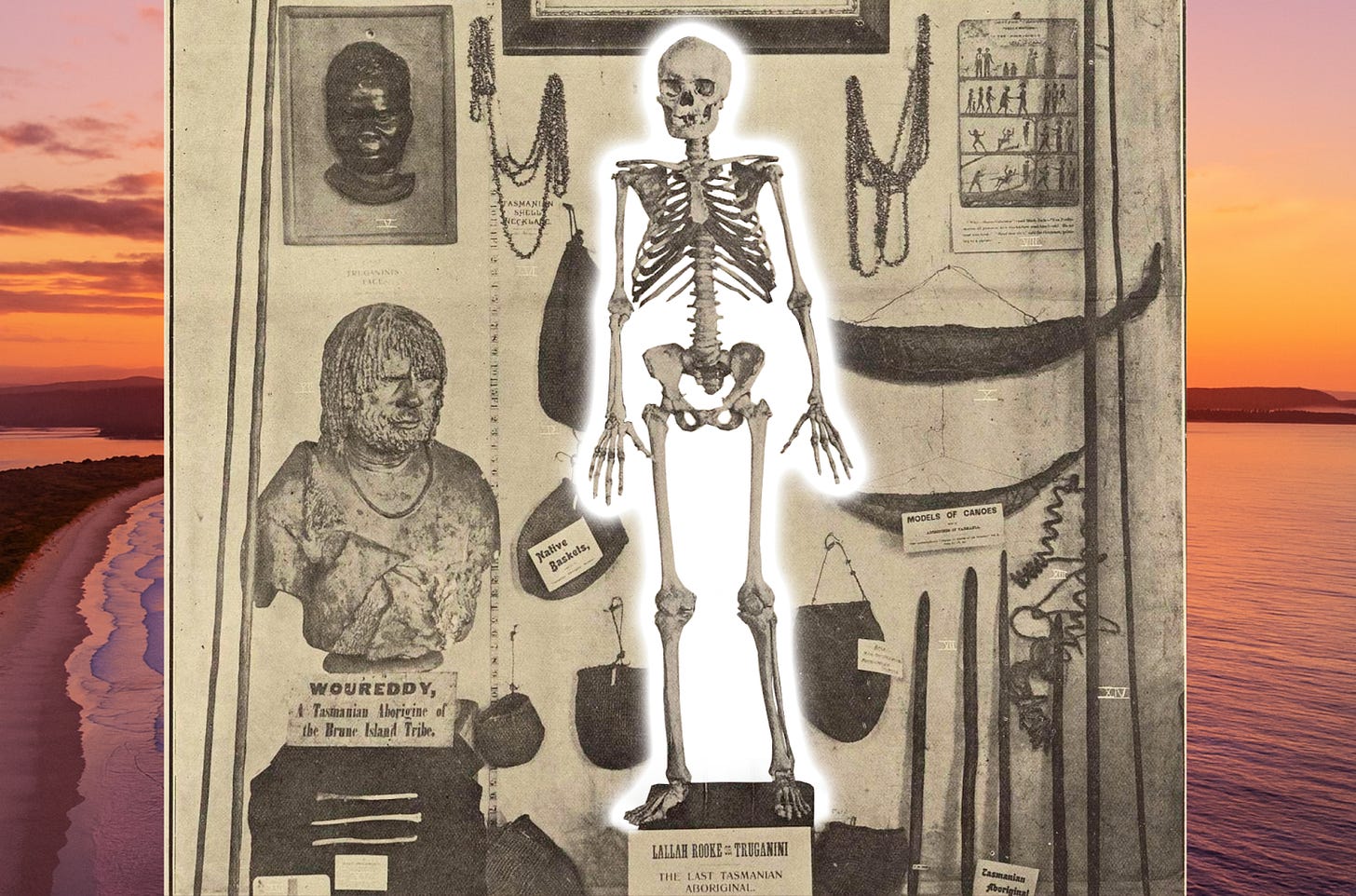

Specifically, it began with renewed demands for the Tasmanian Museum to surrender the remains of Truganini, who had died in 1876. She was known around the world as the “Last Tasmanian Aboriginal”—a claim fiercely denied by Tasmanian activists trying to be recognized as Aboriginal. This now-extinct island population was separated from the rest of the world—including Australia—for 12,000 years and had the simplest toolkit ever recorded in an extant human society, with handheld stone axes and one-piece wood spears. Before their destruction, her bones were one of the last records of her people and their history.

As early as the 1930s, Archdeacon H. B. Atkinson had advocated for her burial but only succeeded in having the bones removed from public display. Then, in 1970, Harry Penrith wrote to the Tasmanian Museum arguing that retaining Truganini’s skeleton was “an insult to the dignity of his race.” That same year, Black Power activist Bob Maza visited Tasmania, where he demanded to see her skeleton, dropping hints about “blowing up bridges” and “polluting water supplies.” A plot was hatched to steal the bones but abandoned due to concerns over violence.

In 1972, Victoria passed its “Archaeological and Aboriginal Relics Preservation Act,” the first state to do so. Such acts governed who could legally own forager remains and would soon be turned against the very archaeologists that had helped lobby for them. This was also the year Michael Mansell and his relatives formed the Aboriginal Information Service, later renamed the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre or TAC.

The TAC’s first major victory came in 1976 when the Tasmanian government overruled the objections of the Tasmanian Museum, cremated Truganini’s remains, and allowed the TAC to scatter them in the sea. The mode of burial was chosen based on her supposed wish to be cast into the ocean because “the Tasmanian Museum want my body.” Other conflicting reports said she asked to be buried in the mountains or beside her father.

Removal efforts now moved beyond named individuals. In 1982, the TAC learned about a collection of forager remains that had been exhumed from the Oyster Cove cemetery by William Crowther. They successfully sued the Tasmanian Museum for their removal and took the bones back to Oyster Cove. Here they performed a “traditional” cremation ceremony and then staged a land rights protest, laying sovereign claim to the now “more sacred” site. The latter event was televised and became a public relations and recruitment win, with the small population of Tasmania’s Aboriginal class more than doubling over the next few years. This watershed moment was what one observer called “a turning point in the Aboriginal struggle,” shifting church and institutional support toward Aboriginal-class causes.

As one scholar notes, “Premeditated or not this proved to be a brilliant strategy, full of emotional and spiritual overtones… Each success further consolidated the Aboriginal community and served to remind the non-Aboriginal community of the inhumanity of their ancestors.“

By 1984, the massive Murray Black skeletal collection had been transferred following legal action by the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service and, in 1985, remains of thirty-eight foragers were buried in a public ceremony in Melbourne’s Kings Domain park.

The movement now targeted fossilized remains with only tenuous connections to contact-era foragers. The ancient skulls from Eagle Hawk Neck and Mount Cameron West (c. 4260 years old) were transferred to the TAC in 1988 and cremated. In Victoria, the Coobool Creek collection was reburied in 1989, followed a year later by the Kow Swamp collection. In 1991, Alan Thorne voluntarily surrendered Mungo Lady, the first individual excavated at Willandra Lakes. During the handover, he implored the 3TTG (Three Traditional Tribal Groups) to preserve the fossils for future generations.

But as the voices of opposition grew weaker, the burials continued: in 2022, both Mungo Man and Mungo Lady were reburied, secretly. The final blow came in March 2025 when the rest of the Willandra Lakes collection, 106 fossilized individuals, was buried in an unmarked grave, despite a last-minute legal appeal from Gary Pappin, a local Mutthi Mutthi man, and efforts by archaeologist Michael Westaway, who compared it to the Taliban’s destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas. As of this year, Australia’s human fossil record, as well as the biological history of many extinct contact-era populations, has been effectively erased.

Motivations and Rejected Compromises

The reasons why scientific and government authorities complied with these demands are complex. Some only did so after lengthy legal battles. Others acted out of personal sympathy, a sense of justice, or a desire to appease the more radical sovereignty agenda seen in the formation of the Aboriginal Provisional Government and the views expressed by Gary Foley in 1972 that “We would like to see separate development for the whites and the blacks—something like that in South Africa. The only thing wrong with South Africa is that the whites are on top.”

The motivations of scientists and institutions are also interesting. Mainland archaeology associations had “abandoned” the Tasmanian Museum in its fight over Truganini, giving up rights over named individuals and dubiously-acquired bones, but then expressed outrage when fossils that had been buried millennia ago—without cremation—were also burned. As more collections became targeted, archaeologists scrambled to draw up ethical and legal guidelines to define ownership, proposing shared custodianship or individual exceptions.

Age-based compromises were also suggested as dividing lines between remains that could be retained for study versus those transferred for burial, such as 7,000 years ago when sea levels rose to form modern Australia. However, these proposals were all rejected.

In general, the activists won the war of words. They used language that bolstered ownership claims like “repatriation,” “return,” and “ancestors,” which implied already-proven connections. While scientists used rigorous but dry terminology, activists referred to bones as “our Old People” whose “spirits cannot rest,” claiming that the mere existence of museum collections caused unverifiable harms like “cultural trauma.” Opponents who accepted this linguistic frame found it hard to argue without appearing callous.

Michael Mansell soon took the campaign overseas, convincing European institutions to hand over remains they had acquired during the colonial period. By the 2000s, the removal movement had won widespread support from museums, governments, and even previously-opposed archaeologists. This shift in attitudes resulted in formal policies and funding that allowed the transfer of thousands of forager remains to Aboriginal-class organizations.

The removal campaign has since gone beyond bones and mummies. In 2009, Mansell argued that two 180-year-old busts of Truganini and Woureddy—her husband— estimated to be worth $700,000, should be “returned” to them as “her image is being used to try to exterminate the aborignal [sic] people in Tasmania,” by spreading the idea that Tasmanian Aboriginal people did not exist (the population was 30,000 in the 2021 census). Art historian David Hansen spoke out in protest, observing that no other museum directors or academics joined him: “Nobody wants to stand up to people whose land was stolen… and say: ‘No, sorry, mate, you’re wrong about this one.’’

In a now-familiar pattern, Hansen endorsed the activists’ claims over sacred items and human remains, but pleaded for an exception to his own field, drawing the line at “secular art” and the TAC’s new demand which stated: “Aborigines find it offensive that images of our dead are still being used without permission. We now write seeking agreement on what items can, or should not, be displayed.”

On the surface, the removal campaign is about justice for historical crimes and the difference between grave robbing and archaeology. But there is something deeper at play. With each success, activists have widened the scope of what could be claimed. The shifting goal posts reveal an existential struggle for self-identity and sovereignty. Perhaps the real battle is over who has the authority to control Australia’s past and, ultimately, Australia.

Science in Australia Has Ground to a Halt

The scientific casualties of this conflict go beyond the loss of research material. Archaeology departments are now filled with researchers who see themselves as working for the Aboriginal class. As one archaeologist recently expressed: “With respect to Aboriginal archaeology, it is not up to archaeologists to determine what the research priorities are, or what stories need to be told.” In this intellectual atmosphere, the few researchers still interested in Australian human origins must approach the topic with caution.

Another Australian archaeologist confided to the author that simply expressing interest in certain topics risks career damage and ostracism. Core claims of the Aboriginal class, such as the continuous occupation of the continent, cannot be questioned. According to this researcher, any study that found evidence of population replacements or regional differences in Denisovan admixture would never be published. It is a paradoxical situation where scientific discoveries must be approved before they are made.

Happily, local Aboriginal land councils have allowed a few accidental discoveries to be briefly studied and dated, such as Kiacatoo Man (c. 27,000 years old), the largest Pleistocene skeleton ever found in Australia. But no intentional excavations have taken place for decades. At the Willandra Lakes UNESCO World Heritage Site, fossilized skulls are occasionally observed eroding from the ground but study is forbidden and they soon disintegrate.

According to archaeologist Colin Pardoe in 2018, “The repatriation of skeletal collections has meant that student access to teaching collections containing Australian material has become almost impossible…. This has resulted in researchers moving into other fields or other parts of the world.” And Vesna Tenodi explains, “Replicas or even drawings cannot be displayed, or discussed, as that also is too offensive without ‘Aboriginal permission.’”

Other archaeologists note that “fieldwork in Australia essentially ground to a halt as much of the modern debate over the origins of modern humans was beginning to take shape.” Just as DNA analysis, 3D imaging, and other revolutionary techniques were entering the field, the fossil record of an entire continent was wiped clean. Only a handful of specimens were ever studied by geneticists. Archaeologist Steve Webb estimated that the Pleistocene series from Willandra Lakes contained 38 individuals suitable for DNA testing. But that analysis was never done and the window of opportunity has now closed.

Many questions that could have been answered years ago remain complete mysteries. It is sadly ironic that we have sequenced the genome of the extinct Tasmanian Tiger before that of Tasmania’s extinct human population.

Also concerning are challenges to the scientific method itself. Language control means researchers can no longer classify prehistoric populations using empirically-verifiable criteria. Instead they can only use approved, nebulous terms like “Aboriginal” and “First Nations.” For example, a recent DNA study disclaims that “Aboriginality is a culturally determined affiliation and not associated with genetic composition,” but then proceeds to talk about “admixture between Aboriginal Australians and Denisovans.” This equivocation between the mixed-ancestry Aboriginal class, contact-era foragers, and ancient Australians causes confusion and makes theories impossible to disprove.

In Australia, free inquiry is now shackled by what senior archaeologist John Mulvaney called the “ideologically enforced glorification of an Aboriginal culture that never existed, but has become the new dogma.”

Looking Forward: Implications and Alternatives

An academic who pseudonymously writes as “Stone Age Herbalist” recently observed: “Unbeknown to most of the public, a new generation of curators and activists are rapidly dismantling the very idea of ‘the museum’ and how they handle and display human remains… Without a robust defence of the impartial scientific gaze, archaeology could easily crumble to dust within our lifetimes.” The centralization of resources that allowed three hundred years of breakthroughs is becoming a liability.

Many people sympathize with Truganini and her reported last wishes. But when the Tasmanian government removed her skeleton, they set the precedent that scientifically-significant remains of foragers could be claimed and destroyed by political activists who were not direct descendants, did not speak their language, did not look like them, and did not even think of themselves as Aboriginal until after 1967.

Now that these activists have acquired most of Australia’s human fossils and bones, they have expanded their removal and censorship campaigns to “include the return of cultural heritage materials, including objects, photographs, manuscripts, and audio-visual recordings.” Each concession leads to more expansive claims rather than resolution. They claim ownership over what questions can be asked about the past and the very words that can be used to ask them.

And the same script is being followed in Canada and the United States, with Indigenous-class activists reburying ancient remains and artifacts under NAGPRA legislation, censoring photographs, and even asserting ownership over dinosaur fossils based on creationist mythology. In 2017, the 9,000 year-old fossil Kennewick Man was buried after years of controversy. In Europe as well, museums and universities face shrinking collections and pressure to censor information.

Everyone agrees that the loss of ancient hominin fossils during World War II was a tragedy. Someday, hopefully, they will feel the same way about the artifacts and fossils currently being destroyed.

Early Aboriginal-class activists identified strongly with the Chinese Cultural Revolution. The comparison is apt considering the countless books and artifacts destroyed under Mao. But the madness passed and today some of the most important discoveries on human origins are being made in China.

There is hope. Some institutions are resisting the pressure to surrender their collections, or at least negotiating DNA analysis prior to removal and burial. Paleoanthropologists are finding mysterious fossils in Southeast Asia, possibly ancestral to the first Australians. A few are building relationships with Aboriginal communities that enable groundbreaking genetics research—although hypotheses, conclusions, and data are still restricted. Others have performed DNA analysis as a way to help the reburial movement, identifying where remains originated. And across the world, independent scholars and collectors are joining forces to learn and preserve what they can.

It should be remembered that many descendants of Australian and Tasmanian foragers value the scientific method and wish to know the truth about their ancestors. While they are not as vocal or powerful as their government-recognized “representatives”—some don’t even identify as Aboriginal—they exist and more will join them.

The exploration of humanity’s past belongs to all of us regardless of political class or family tree. When truth is determined by authority, not evidence, we risk enshrining falsehoods and fantasies, something that will inevitably exact a cost on our society. But while ideologies rise and fall, the story written in our bones and DNA stays unchanged, waiting to be read.

Jack Mungo is an American independent researcher who is trying to find out what actually happened in prehistoric Australia. You can follow him at @MungoManic.